Today, Star Trek is an institution, a permanent part of our cultural fabric. There have been over a half dozen television series, twice as many movies, as well as countless novels and comic books. The original U.S.S. Enterprise model hangs in the Smithsonian. The shuttlecraft Galileo prop is on display at NASA in Houston. Astronauts and scientists credit Star Trek as inspiring their career choices. “Beam me up, Scotty” is a worldwide catch phrase.

But in 1972, Star Trek was dead.

The network had cancelled what is now referred to as Star Trek TOS in 1969 after three years of lackluster ratings and high costs. Captain Kirk and the crew were furloughed and the U.S.S. Enterprise put in mothballs.

Then the show went into permanent reruns and found a new and expanding audience. Start Trek conventions popped up. Fanzines spit out of mimeograph machines. A comeback seemed imminent.

But while the spirit was willing, the financing was weak. Ponying up for a reunion with Gene Roddenberry wasn’t getting past the Paramount bean counters.

That changed with an announcement in 1973.

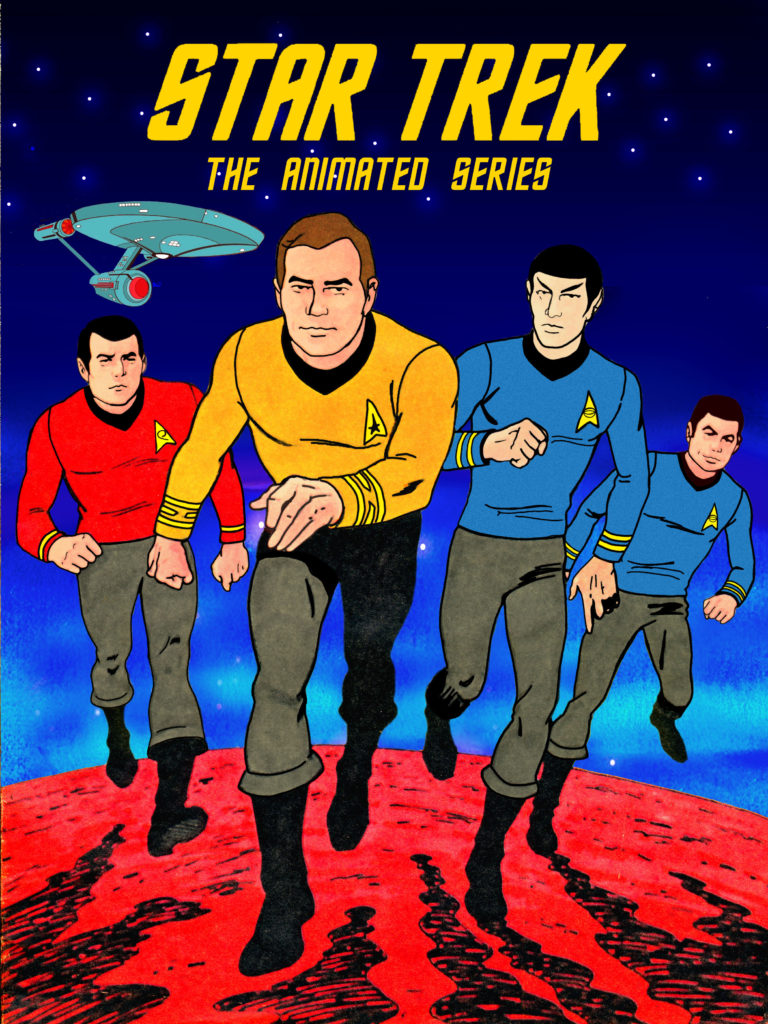

Star Trek would return to the air on a late Saturday morning in September. As a cartoon.

I was a Trekkie. Only seven years old during the show’s last season, I remember being sent to bed at 9 pm on Friday nights just as the Enterprise entered orbit around some distant planet. In my bedroom, starship models hung from my ceiling. Paperback versions of the TOS stories lined a shelf. I dressed up as Spock on Halloween.

I remember having been gripped by anticipation all summer awaiting the September premiere. Shatner, Nimoy, Kelley, Doohan, Nichols, Takei, and Barrett would all be back at their stations. Only Walter Koenig would miss the departure of the Enterprise out of space dock. There was great potential here. Writers from the original episodes had signed on to create new content. D.C. Fontana was managing scripts. Expensive special effects could be cheaply done with animation. Star Trek could be back on a budget. The adventure would continue, twenty-two minutes at a time.

I watched, glued to the set every Saturday. I remember getting furious when the same episode seemed to rotate in after only a few weeks. I also remember a bit of disappointment. Lt. Arex, a bright red tripod creature, was filling Checkov’s chair, and sometimes a purring cat-like Lt. M’ress subbed for Uhura. They didn’t do anything for me. I also felt that the stories had been watered down a bit for a younger audience. The fact that I was eleven and was that younger audience did not seem to register.

Then as quickly as it came, it was gone. Eighteen episodes in Season One were followed by only six episodes in Season Two and suddenly, Star Trek had been murdered twice. I was crestfallen. It would take four more years for the five year mission to re-start with Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

I came across the animated series on Netflix, our video version of Memory Alpha. I decided it was time to slingshot around the sun, time travel back to groovy ’73, and see how well this bit of crushed Federation hope had held up. I settled into the couch and hit play.

The first episode starts, and it is like opening a time capsule. Kirk and the crew’s voices are perfect, in character and sounding just like they did in 1966. The format, from Captain’s Log entries, to the background music, to the set designs, are all lifted straight from the series. There is no re-imagining, no updating. These parts of Star Trek weren’t broken, so no one fixes them. If I close my eyes, it is like listening to deleted scenes from the original series.

The problem is, I can’t close my eyes.

The animation is horrendous. Not just low-frames-per-second-poor like so much TV animation, or lacking in detail. This work is sloppy. The insignia on characters’ chests switch sides during scenes. Dr. McCoy is shown on the bridge just before Kirk calls sick bay to talk to him. Kirk’s hair part moves from right to left. In one scene his eye disappears for a split second. Some kind of glare or dirt follows the Enterprise as it crosses the screen. There are mind-numbing errors in almost every episode, as if the animators only had two days to make the show and once the first draft filled twenty-two minutes, there wasn’t time to do much more.

The voice budget already spent, Majel Barrett appears to have been pressed into service for every female character, from the cat girl comm officer to any alien that drops by. And while James Doohan was the master of a hundred accents, she is not.

Then there are the scripts. Considering the limited amount of screen time available, about half of them are pretty good, and several could have been fleshed out into a Star Trek TOS Season Four episode. We get another round of tribble fun in one, and Harcourt Fenton Mudd is back in another. But many are near unwatchable, including one penned by Walter Koenig. Plot holes, transparent premises, inconsistencies. If they were all this bad, that would be one thing, but the fact that some were good says that the poor ones never should have made it into production.

If you aren’t a true fan steeped in the 1960s version of Roddenberry’s universe, then it’s likely that viewing this reboot-before-we-had-reboots won’t be worth the time. Even though it bears a Roddenberry imprint, its position in official Star Trek canon is in doubt, and for good reason. In fact, it is not listed at the official Star Trek website as one of the television shows. But as an historical fan oddity (like The Star Wars Christmas Special but in a much better way) those who like their Spocks with beards and their red shirts expendable might want to give the show a whirl. Beam down and explore episodes Yesteryear, More Trouble with Tribbles, and The Terratin Incident. Treat One of our Planets is Missing, The Infinite Vulcan, and The Practical Joker like quarantined planets. The rest are somewhere in between.

Live long and prosper.